This content was originally published by the Longmont Observer and is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

Longmont has some skeletons in its closet that nobody likes to talk about. Those skeletons have to do with when the Ku Klux Klan held sway in town and in Colorado in general. In the 1890s, there was an organization very similar to the Klan active in the area called the American Protective Association.

By June of 1921, Denver announced the formation of a Klan branch but it went underground shortly thereafter. The branch reappeared in January of 1922, and because the public did not protest, it grew. Within two years of coming to Colorado the clan had 50,000 followers.

After WWI, many men returning from the war felt they had accomplished little. Totalitarianism was on the rise in Russia among other things. Frustrated, the men turned their anger on foreigners and the Klan became attractive. Recruitment in Colorado was easy along the Front Range due to the density of the population, and therefore an intense recruitment campaign was carried out.

In the same era, the mining and agricultural industries were experiencing financial difficulties, and this, along with a feeling there was a lack of social roots in the community, was exploited for recruiting purposes. At the time, one third of Methodists, one quarter of Baptists and over two thirds of Disciples of Christ had links to the Klan.

Across the Front Range, crosses were burned on synagogue lawns and the lawns of Catholics. In 1923, the Klan brought Bishop Alma White to the Pillar of Fire church in Longmont to speak about the Klan and against the Catholic church. When a local newspaper objected to the anti-Catholic speech, it was boycotted. The Klan was known to go into sympathetic churches during services and presenting the pastor with gifts of money.

The Klan’s local branch in Longmont was called Klavern No. 2. They frequently held rallies on the southeast corner of 3rd and Martin Street in what was then an open field. At one point, a dozen armed Hispanic men showed up at one of the meetings led by José Hilario Cortez. The men warned the Klan members that if anybody in the Hispanic community was harmed all the men would retaliate.

Dr. G.C. Minor from Atlanta, a well-known Klan lecturer, came and spoke to a large crowd on 4th Avenue about the Klan. The Longmont Ledger reported in 1924 that hooded and robed figures were seen at a Klan meeting at the auditorium in Roosevelt Park. Public lectures about the Klan were also held at the auditorium.

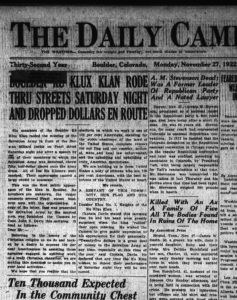

In June of 1925 a “mammoth Klan parade” was held in Longmont with members from all over the northern part of the state attending and parading down Main Street. The demonstration included hooded men on horseback, and approximately 500 men on foot. After the parade, a large cross was burned in the open space south of the city after the parade during an initiation ceremony.

In 1923, some Klan members were elected to the Longmont city council, but there were not enough for a majority. Even more were elected in 1924, but the Klan still did not have a majority. Klan members on the council got rid of the position of city engineer, putting E.S. Bice out of work after eight years in the position. At this time, the Klan in Longmont was large enough that they could send 50 members to attend a Klan funeral in Lyons. In December of 1924, the Klan erected a large red cross on the Christmas tree at 4th and Main which stayed there for two days.

Running on the Progressive Economic ticket in 1925, the Klan finally managed to elect a majority to the city council. The mayor, four aldermen, and the treasurer were all Klan members. The Klan-led council promptly got rid of the street superintendent who had worked for the city for 38 years. They also got rid of the fire chief, a 15-year veteran of the fire department who had been chief for seven years. The fire chief was replaced with a Klan sympathizer. This pattern of firing officials and replacing them with Klan-friendly officials was not uncommon.

It was not until the Klan attempted to run for school board that the public spoke out against them. The Daily Times said, “Not content with the spoils which have come to them through control of all departments of our city government, the local leaders of the so-called ‘Invisible Empire’ are now reaching out for control of our schools.” The paper called on people to form a “Visible League” to keep the Klan out of the schools, but two members of the Klan were elected to the school board nonetheless. The Klan offered a reward of $100 in 1925 for information leading to the discovery of the person spreading rumors that the Klan was opposed to a bond measure to build new schools.

Citizens became concerned about the rising cost of the dam and eventually, a state engineer was called in to review the plans. The state engineer estimated the dam would actually cost $350,000 to build making it financially prohibitive. He concluded that the dam would be empty before the summer was over so building a hydroelectric dam wasn’t practical. Water purity was also concluded to be an issue. The dam was eventually abandoned. The concrete foundation of the dam is still visible today.

Fed up with the Chimney Rock Dam fiasco, citizens voted the Klan out of the city council during the 1927 elections. Fred Flanders was elected mayor on an anti-Klan platform. Although diminished, the influence of the Klan continued to be felt in Longmont throughout the 1930s and 40s. There were cross burnings reported in the 1930s. During 1940, it was well-known that the Klan regularly held meetings in the foundry at the south end of Martin Street just past the Kuner-Empson packing plant. The police chief at the time, Orval Barr, was a Klansman who attended meetings at the foundry.

Although its influence is greatly diminished, the Ku Klux Klan still exists in the state of Colorado. It is important to remember when the Klan ran Longmont. As Maya Angelou said, “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”